Connect with me

Creational Design Pattern: Builder

The Builder pattern helps create complex objects step-by-step while keeping them immutable and enforcing any required rules. It avoids messy constructors, makes code more readable, and is perfect when you have both required and optional fields.

This article is part of a series exploring design patterns using the Java programming language. The goal of this series is to help readers develop a solid understanding of design patterns while also sharing real-world examples from actual codebases that make use of these patterns.

In this article, we’ll be discussing the Builder pattern.

Symbols for better navigation:

🤔 Hypothetical Scenario/Imagination

⚠️ Warning

👉 Point to note

📝 Common Understanding

Builder Pattern

The Builder design pattern allows for the step-by-step creation of an object while maintaining the contract rules for that object.

It is often desirable for an object to remain immutable after it has been created, meaning its properties should not change once it is instantiated.

🤔 If we think of a Java bean object that needs to be immutable after instantiation, the simplest approach would be to remove all setter methods and only keep constructors.

public class MyClass {

int myVar;

public MyClass(int myVar) {

this.myVar = myVar;

}

// --> Remove setters to force immutability

// public void setMyVar(int value) {

// this.myVar = value;

// }

}This way, we can set property values once during construction.

However, this is not always a suitable solution.

One drawback is that if the object has many property variables but only a few of them are mandatory, we would end up writing and maintaining multiple constructors to cover every combination of arguments.

📉 This makes the code harder to read, maintain, and extend.

public class MyClass {

int myVar;

int myVar2;

int myVar3;

// ... more properties

public MyClass(int myVar) {

this.myVar = myVar;

}

public MyClass(int myVar, int myVar2) {

this.myVar = myVar;

this.myVar2 = myVar2;

}

public MyClass(int myVar, int myVar2, int myVar3) {

this.myVar = myVar;

this.myVar2 = myVar2;

this.myVar3 = myVar3;

}

// ... more constructors

}Additionally, if certain properties must always be set during instantiation, we need a way to enforce that requirement.

We might think of putting the validation logic inside the constructor body and throwing an error if the user fails to meet the criteria.

public class MyClass {

int myVar;

int myVar2;

public MyClass(int myVar) {

this.myVar = myVar;

}

public MyClass(int myVar, int myVar2) {

if (myVar2 == null) {

throw new Exception("Var 2 is required"); // enforcing contract

}

this.myVar = myVar;

this.myVar2 = myVar2;

}

}But this quickly becomes messy:

- Constructors are not ideal places for complex business logic.

- The same validation code may be repeated in multiple constructors.

This is where the Builder design pattern comes to the rescue.

This design pattern does two things:

- Force Immutability to the object post creation.

- Establish contracts that need to be fulfilled for successful creation.

Recipe to cook the Builder pattern for any object

Once you know you have a scenario where the Builder pattern is appropriate, the next step is to create a builder for that object.

A builder class contains the logic to:

- Instantiate the object once all requirements are met.

- Set required and optional property values.

- Enforce any rules or contracts before the object is created.

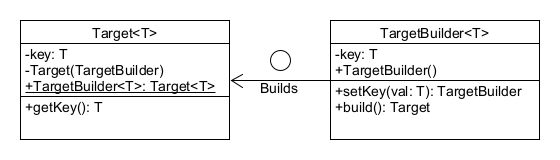

Suppose we want to instantiate a Target class. We can build a TargetBuilder class as follows:

- Create the

Targetclass and declare all its properties asprivate. - Create a public static inner class within

TargetnamedTargetBuilder. - Add a private constructor inside

Targetthat accepts aTargetBuilderinstance. - Inside

TargetBuilder, add setter-like methods for each property. These methods returnthisso that calls can be chained. - Create a

build()method inTargetBuilderthat:- Validates all required properties.

- Creates and returns a new

Targetinstance.

After implementing these steps, the Target class follows the Builder pattern template.

public class Target<T>{

private T key;

private Target(TargetBuilder builder) {

this.key = builder.key;

}

// builder class

public static class TargetBuilder<T> {

private T key;

public TargetBuilder() {

}

public Target build() { // <-- Builds/Construct the class

// ...logic to enforce contract here

return new Target(this);

}

public TargetBuilder setKey(T value) {

this.key = value;

return this; // method chaining

}

}

// getter methods, but no setter methods

public T getKey() {

return this.key;

}

}

The builder for Target can now be used as follows.

public class Test {

public static void main(String[] args) {

TargetBuilder<String> builder = new Target.TargetBuilder<>();

builder.setKey("Amrit");

Target target = TargetBuilder.build(); // object construction

// target.setKey("Amrit2"); // mutability not allowed!

}

}Real-World Use of Builder

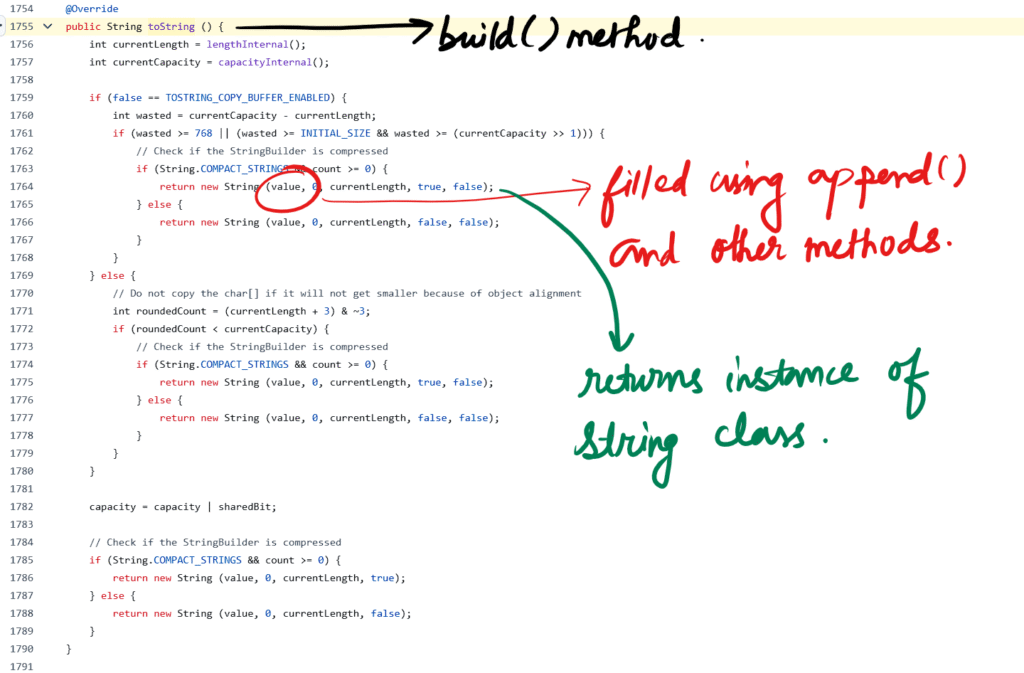

One of the most familiar examples of the Builder pattern is found in the Java JDK — the StringBuilder class.

Here’s basic usage of the StringBuilder class to construct a String.

public class Test {

public static void main(String[] args) {

StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder();

sb.append("Amrit");

sb.append(' ');

sb.append("writes well.");

String message = sb.toString(); // Amrit writes well.

}

}Here’s what happens:

- When we call

toString(), it works like thebuild()method, producing the final immutableStringobject. - The values (strings, characters, etc.) are stored internally in a variable (usually named

value). - The

append()anddelete()methods act like the builder’s setter methods.

If we peek into the java.base source code, you’ll see that the toString() implementation constructs and returns the final string, just like our TargetBuilder.build()

Up Next in the series

Subscribe to my newsletter today!