Connect with me

Behavioral Design Pattern: Chain of Responsibility

This article is part of a series exploring design patterns using the Java programming language. The goal of this series is to help readers develop a solid understanding of design patterns while also sharing real-world examples from actual codebases that make use of these patterns.

In this article, we’ll be discussing the Chain of Responsibility pattern.

Symbols for better navigation:

🤔 Hypothetical Scenario/Imagination

⚠️ Warning

👉 Point to note

📝 Common Understanding

Chain of Responsibility Pattern

The Chain of Responsibility pattern lets you decouple the sender of a request from its receivers by giving multiple objects a chance to handle the request.

Each handler in the chain:

- Either handles the request or forwards it to the next handler

- Performs some check or operation

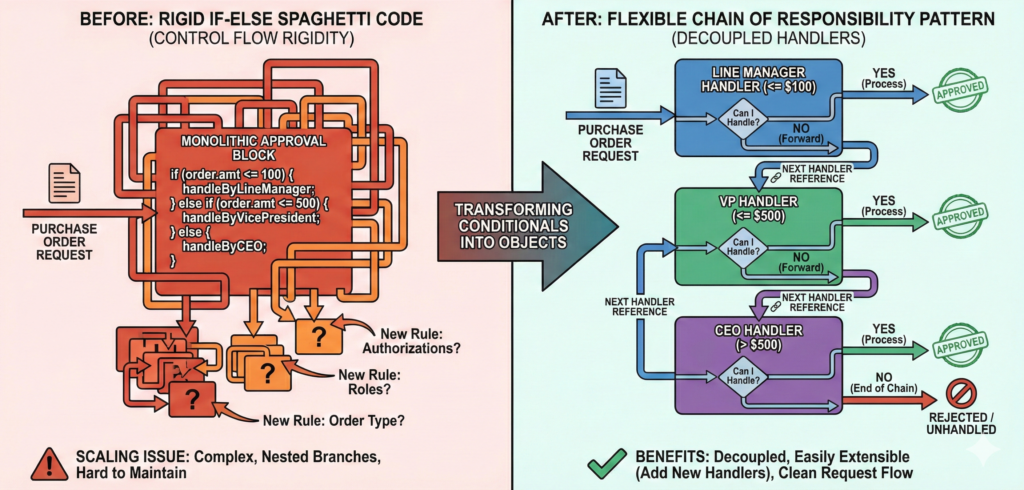

🤔 Imagine you are writing code that processes incoming requests for purchase order requisitions.

These orders have tobe passed on by to the top beginning from the bottom, with the line manager all the way up to the CEO.

However, there’s a catch. Not all the approvals need to go all the way up to the top i.e. for orders which are less than 500 USD can be approved by the VP, and orders less than 100 USD can be approved by the line manager.

You might start simply like this:

if (order.amt <= 100) {

handleByLineManager(order);

} else if (order.amt <= 500) {

handleByVicePresident(order);

} else {

handleByCEO(order);

}This if-else spaghetti code looks good until it won’t.

As the requirements of multiple type of validations happen like: authorizations, roles, type of order etc. the if-else condition will be tightly checking each and every rule and thus will lead to even more if-else branches, maybe even nested ones.

👉 The real issue here is control flow rigidity.

The Chain of Responsibility pattern fixes this by turning conditionals into objects.

Instead of one method deciding everything:

- Each responsibility becomes its own handler.

- Handlers are linked together as a chain.

- The request flows through the chain until it is handled.

Each handler has:

- A reference to the next handler.

- A method to process or forward the request.

if-else logic into the Chain of Responsibility pattern. This transformation decouples request handlers, making the system easier to maintain and extend as business rules grow.Recipe to cook the Chain of Responsibility Pattern for objects

To implement this pattern cleanly, follow these steps

- Define a handler interface or abstract class.

- Create concrete handlers and store a reference to the next handler.

- Build the chain: Let each handler either handle the request or delegate to the next handler.

abstract class Handler {

protected Handler next;

public Handler setNext(Handler next) {

this.next = next;

return next;

}

public abstract void handle(Request request);

}

Case-Study

Suppose we are building an API backend.

Every request must pass through:

- Authentication

- Authorization

- Business validation

Each step is independent, ordered, and optional.

This naturally forms a chain.

Step 1: We begin by forming our common request body.

class Request {

String user;

boolean authenticated;

boolean authorized;

}Step 2: Concrete Handlers from our abstract handler shown above.

class AuthenticationHandler extends Handler {

@Override

public void handle(Request request) {

if (!request.authenticated) {

System.out.println("Authentication failed");

return;

}

System.out.println("Authentication passed");

if (next != null) next.handle(request);

}

}class AuthorizationHandler extends Handler {

@Override

public void handle(Request request) {

if (!request.authorized) {

System.out.println("Authorization failed");

return;

}

System.out.println("Authorization passed");

if (next != null) next.handle(request);

}

}class BusinessLogicHandler extends Handler {

@Override

public void handle(Request request) {

System.out.println("Business logic executed");

}

}Step 3: Build the chain

public class ChainDemo {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Handler auth = new AuthenticationHandler();

Handler authorization = new AuthorizationHandler();

Handler business = new BusinessLogicHandler();

auth.setNext(authorization).setNext(business);

Request request = new Request();

request.authenticated = true;

request.authorized = true;

auth.handle(request); // Result: Business logic executed

}

}Common Pitfalls

⚠️ Request may go unhandled: If no handler processes the request, it silently passes through.

⚠️ Debugging can be tricky: Flow is distributed across objects.

👉 Use this pattern when order matters and logic must stay decoupled.

Up Next in the Series

Command Design Pattern

Subscribe to my newsletter today!